What is a Commercial Vessel?

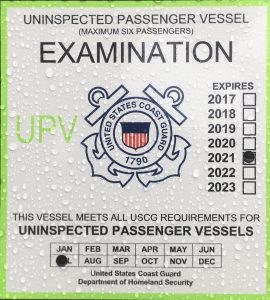

A friend recently asked about Condor’s commercial inspection. I clarified that Condor is an Uninspected Passenger Vessel and goes through an examination rather than an inspection. While it may seem like semantics, there is more to it than that.

First, let me explain why Condor is a commercial vessel and not a recreational vessel. We take paying customers onboard, so Condor has to be documented or registered as a commercial vessel. If one person pays to be on the boat, the vessel has to be a commercial vessel. Even if the captain or owner of the boat doesn’t receive a cent, as may be the case with a nonprofit organization like SeaAffinity, the boat still needs to be commercial. We are not willing to risk facing a $60,000 fine!

There are several levels of commercial vessels. The two most common are Inspected and Uninspected. The differences are as different as the name. While there are requirement for both, Inspected boats are required to go through a rigorous periodic inspection to maintain their Certificate of Inspection (COI).

Inspected Vessels

Inspected vessels are generally permitted to carry more the six passengers. They have a long list of stringent requirements to maintain that ability. These include stability tests, solidly encased tankage, permanently installed fire suppressant systems, life boats, higher life lines, and many others. It would be easy to spend $20,000 to bring a vessel up to these standards. When consider a 36 foot vessel, such as Condor, we would not want more than six passengers due to comfort and space. There would be no financial benefit to obtaining a COI for more than six passengers since we would not take more than six anyway.

Uninspected Vessels

There is a vast difference between a recreational vessel and an uninspected passenger vessel. From outward appearances, they may look the same, but there are a few telltale differences. (I will go into them later.) While the US Coast Guard is not required to come on board and check things, they still can.

Manning: An Uninspected Vessel must be manned by a USCG licensed captain. They must have a copy of their license on board. The captain is limited to 12 hours on watch.

Drug testing: The captain and crew must have evidence of participating in a drug-testing program. This includes pre-employment and periodic random testing. It also includes probable cause testing. For instance, if there is an accident or an injury requiring more than first aid, the captain needs to be tested. The vessel also needs to have a drug policy posted.

Trade Eligibility: There are two options here. If the vessel is less than five Net Tons, it can be registered with the state as a commercial vessel. This is the case with our Novurania that we use for powerboat training. (Please note that Net Tons is not weight, but rather a measurement of volume – how much cargo it can carry). Our powerboat is state registered as a commercial vessel and is insured to carrying passengers and for teaching.

If it is over five Net Tons, it has to be documented with the Coast Guard as a commercial vessel. It also requires endorsement for Coastwise Trade, which seems a little strange for a boat teaching lessons or taking guests out for a couple hours.

With both of these options, the boat must be U.S. owned and U.S. built. This stems from the Jones Act. Does that rule out all foreign-built vessel from operating as a UPV? No. Owners of boats built outside the U.S. can apply for a MARAD waiver, pay a $500 filing fee, and hope the Federal Government approves the application.

Vessel Papers: UPVs are required to carry their state registration or USCG documentation onboard. As mentioned above, if the bot is more than five Net Tons (or about 30’), it has to be documented and not only display its name and hailing port on the stern, it has to have its name on both sides of the bow in four inch letters. (That is one of the visual distinctions I mentioned in the opening.)

Safety Orientation: UPVs are required to give a verbal safety announcement prior to getting underway. They are also required to have instructive placards.

Lifesaving Equipment: That bag of type II PFDs getting moldy in the bottom of the locker are not going to cut it. UPVs are required to have those big bulky Type I offshore PFDs. Vessels also are required to have an orange of white ring buoy. In addition, all of these must bear a mark from the USCG approving them for commercial use.

Fire prevention and Suppression: Vessels operating as UPVs must meet stricter guidelines than those for recreational vessels. This includes not only fire extinguishers, but also combustibles.

Other Stuff: Rather than listing every requirement for UPVs, I’m going to point you to the USCG UPV Guidebook that goes into a detailed listing of the requirements. You can find that publication here – https://homeport.uscg.mil/Lists/Content/Attachments/1600/UPV_JobAid2011.pdf

But There is More!

The USCG UPV Guidebook doesn’t mention insurance. While you technically could operate a UPV without insurance, I would not be wise. One little accident or even a misstep could lead to a lawsuit. A vessel or operator that is not properly insured could end up losing everything.

From the passenger’s perspective

How do you know if that boat you are getting on is legal to take paying customers? Does it even matter? It may! First, all of the above information outlines some of the requirements for commercial vessels. For your safety, it is a good idea to ask to see proof of these before getting on board. If the captain hesitates to produce any of it, it is probably a good sign that they are not legal.

Whether they are legal matters most if there is an accident. Granted, the chance of an accident is pretty slim, but that it why they are accidents. No one plans to trip over a line and break their arm. However, these things happen. When you try to file a claim against the vessel’s insurance, you may be surprised to find they are not covered. Yes, you can sue, but since they are not covered, you may not end up with much of value to you.

If a vessel is taking passengers, it needs to have a charter insurance policy. If they are teaching lessons, they need an endorsement for that. The underwriter should ask a copy of their documentation to make sure they are legal. They will most likely ask for a current survey of the vessel to make sure it is in acceptable condition.

Getting back to the telltale indicator of a commercial vessel, if they do not have the vessel name on the bow, there is a high chance that it is not a commercial vessel. Moreover, if it is not a commercial vessel, they are most likely not properly insured.

You can be confident that when you book a sailing charter, sailing lesson, or powerboat lesson with SeaAffinity, the vessel you are on is legal and properly insured for your safety.

How long does it take to learn to sail? We hear that question frequently. In a sense, it is a hard question to answer because there are so many variables. We have a short answer, which we will share in just a moment, but first, we want to show why it is a hard question to answer.

How long does it take to learn to sail? We hear that question frequently. In a sense, it is a hard question to answer because there are so many variables. We have a short answer, which we will share in just a moment, but first, we want to show why it is a hard question to answer. It is hard to pin an exact date and time to our beginning of the concept of SeaAffinity. Yes, we can pin the exact date to the incorporation of the organization – February 8, 2012. However, our beginning started long before then.

It is hard to pin an exact date and time to our beginning of the concept of SeaAffinity. Yes, we can pin the exact date to the incorporation of the organization – February 8, 2012. However, our beginning started long before then.